Puzzling Conversations: Gus – Part Two

Tonight we continue our conversation with Gus, a retired IT guy from New South Wales, Australia about what determines puzzle difficulty. As many of you probably know, Gus is a pretty prolific writer, especially on the topic of puzzles. So, in the not so distant future I will be sharing more of his thoughts on all things puzzling. Hopefully you will find his commentary as insightful and entertaining as I have.

PM: How do you define puzzle difficulty, Gus?

GUS: To explain difficulty, I need to diverge a bit. I tend to rate things in groups, rather than try to define a specific place, or ranking order. The problem with ranking order is that it eventually becomes comparative, and you end up discarding most of the information anyway. What I mean is, say you are rating movies for example, and say you choose to use a scale of 1 to 10. What you will find is that two things will happen quite quickly. The first is that you will end up using halves, so you are actually using a scale of 1-20 (eg. you start rating 6.5 and 8.5) The other thing is that you will probably never score a movie a 10, after all, what’s perfect, and while you might score the occasional 1, you won’t really use 2, 3 or 4 much. Most stuff will be 6 or 7 or 8, so why bother with 10, and why bother with 20 (10 and halves!) But it gets worse, because what will happen over time is you will watch a movie, call it “A” give it say a 7, then realise that you gave a different movie, call it “B”, a 7 last year, and A was better than B, and since you can’t use halves… oh no, so does A get bumped, or B dropped! My solution fixes that dilemme, and can be applied to anything. In movies, it is…

1. Didn’t make the end

2. Made the end but only just

3. Liked it

4. Loved it

5. Best movie ever, watch it

Easy now to rate things They belong in groups, rather than trying to assess whether thing A is better than thing B. Thing A might be better than thing B, but if they were both approximately the same level of enjoyment, then they belong in the same group.

So…I rate puzzles:

1. Too easy

2. Easy

3. Medium

4. Hard

5. Too hard

Sure, you could reword these to be easy, medium, difficult, very difficult, and impossible, but the words don’t matter as much as their relative places.

PM: Very interesting insight, Gus. I have followed a 1 to 5 scale for movies and books for years because I have always thought a 1 – 10 scale was far too many. Your group rating does make a lot of sense, especially when it comes to puzzles and something I had never thought of doing – until now.

GUS: I tend not to do puzzles that I would say are too hard. They just aren’t fun, they are a task, a slog, and yes, you get the big reward at the end, but was it worth it? We all have our own idea of what constitutes difficulty, and mine will be different to yours, it is after all subjective, but how hard a puzzle is depends a lot on your level of experience. If a puzzle is too easy, it really isn’t much fun at all. I did one recently that was too easy, it was almost boring. The occasional easy puzzle is fine, but for me, I am more into medium and hard. Medium is good, hard balances out with easy

I like to mix the degree of difficulty as well as subject matter, and piece count. It is worth noting that I mention piece count separately to degree of difficulty, because they are two different things. Many people seem to equate piece count with difficulty. That is not unreasonable by the way, because up until fairly recently, I would have assumed the same thing, but two things happened that made me realise they aren’t.

The first is that because of current trends (which we will delve into later) I found that there just aren’t any new puzzles to buy, so I had to do something I’d never considered before, namely, buying small puzzles, and by small, I mean under 3K pieces. I was doing a John William Waterhouse 3K puzzle at the time, called Echo and Narcissus. I would put it in my hard category, but it was very enjoyable. Then, since I loved it so much, I followed it with a 1K Waterhouse puzzle that I just bought, Soul of the Rose. I didn’t give it any thought when I first started, but as I was putting it together, I realised that it was every bit as “hard” to do as the 3K, and then the obvious next conclusion wasn’t a great leap. Same artist, same style of painting, why would it be any different, regardless of the piece count. Ok, obviously if you go to very low piece counts or very high ones, the difficulty is going to change slightly, but difficulty and time taken are not the same thing. Clearly, larger piece counts take longer, but that doesn’t mean they were more difficult. Difficulty to me is essentially “how easy or hard is it to put the pieces together?” Notice that I didn’t say “to look for a piece” because it is obvious that IF you are looking for “a” piece, then looking for “a” piece in amongst thousands of pieces is much harder than looking for the same piece among hundreds. I write all this to explain why I am saying a 4K puzzle (Oberhofen or Amsterdam) is harder than the 6K puzzles I mention doing earlier. In fact, I was recently doing a 5K puzzle (Educa 18015 – The Harbour Evening) while my visiting daughter was doing a 1K Eurographics puzzle (Eurographics 6000 0690 – Desert Dreams) and after swapping between the two, it was obvious to me that her 1K puzzle was way harder than my 5K. Go figure eh?

PM: So, if it isn’t piece count that makes it difficult, what does?

GUS: Two things, well, more than two really, but that can be for another time, two MAIN things. The image itself, which is pretty obvious and most people will get it, and ‘the cut’, which is more esoteric and deserves its own explanation, but that also can be dealt with in more detail later.

Editor’s Note: The following paragraphs refer to the three difficult puzzles Gus mentioned in Part 1 of our conversation. I am adding them again here as an easy reference point.

Amsterdam: Suffice it to say that Waddington’s cut is very difficult, and when you combine that with a lot of sky, and the fact this is a painting, you end up with something that is approaching my ‘too hard’ basket. If this was say an Educa, or Clementoni, or Ravensburger, or most other (GRID CUT!) brands, then it would change. You put these three factors together (cut, sky, painting), you have a hard puzzle. BUT, I did this a long time ago. Not sure where it is or who I gave it to, but I no longer have it. I did luck out recently and score a sealed copy of it, and plan to do it soon. Whether now, with 35 years’ more experience I find it simpler, remains to be seen. For now, it is definitely one of the hardest I have ever done.

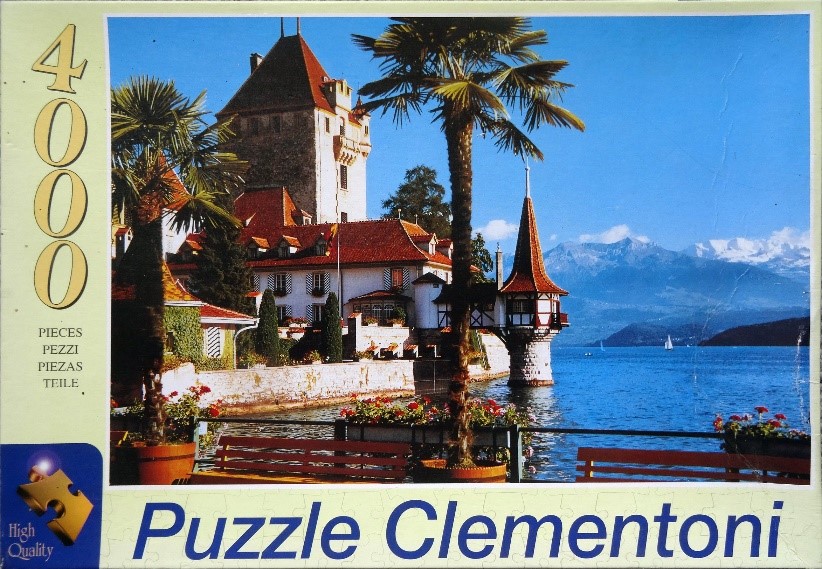

Oberhofen: Sky. Says it all. Solid. Blue. Sky. Lots. Brute force. No other way. I didn’t even use the pattern. If I was doing it today, I would.

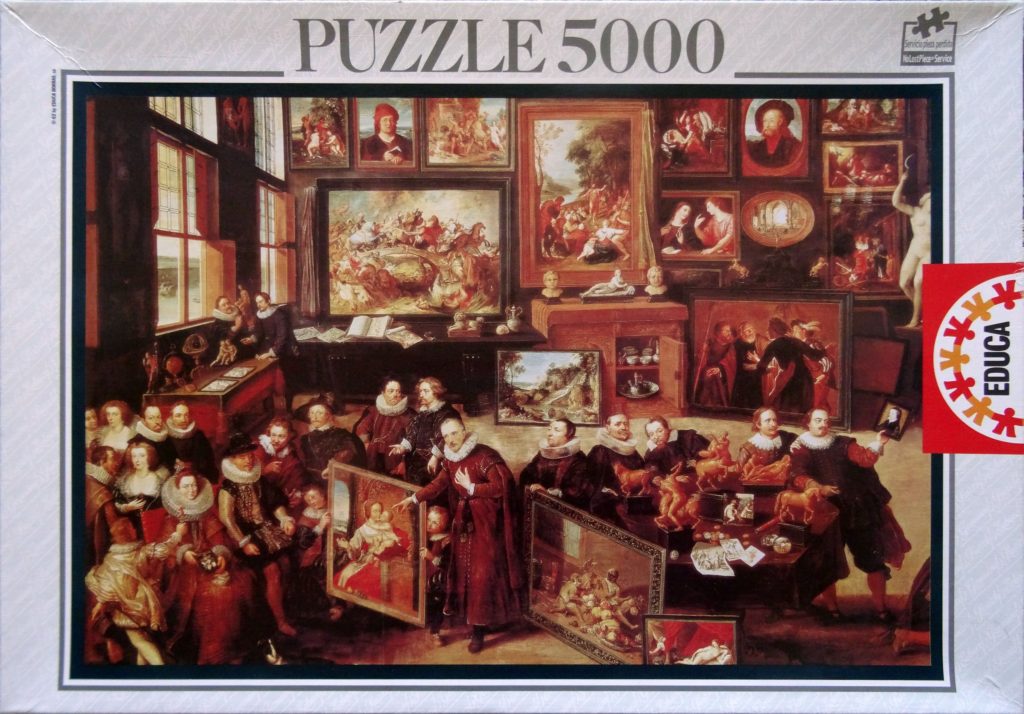

Educa Gallery: A lot of brown. And black. And brown. The Educa cut both hinders, and helps, and that border was the hardest border I’ve ever done, bar none, without a doubt. Solid, unchanging, black, with a zillion interchangeable pieces, some that are so close, yet not, I knew at the time they were wrong, and planned to go back at the end and fix them. I actually forgot to do this, and it was only when I was tidying up my pics in Photoshop, that I noticed some pieces were in the wrong place! Moral: don’t forget to check your work at the end if in doubt

To me, this was a very satisfying puzzle. It was hard, but not so hard that I couldn’t always put a piece or two together. It was just the right degree of hard for me. Immensely satisfying.

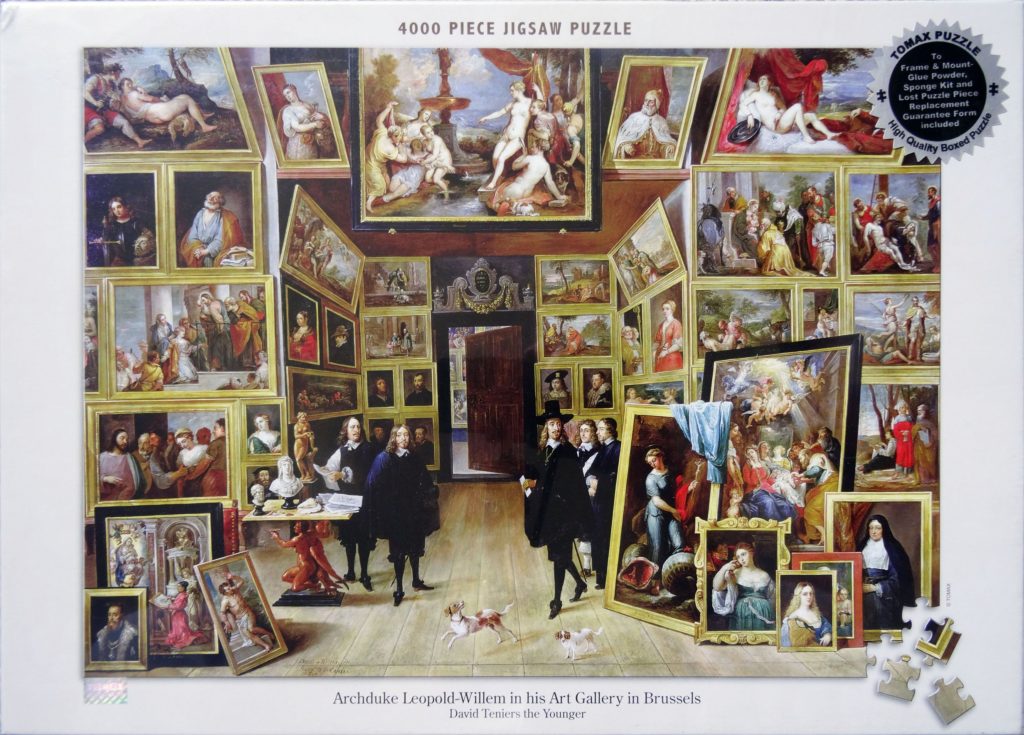

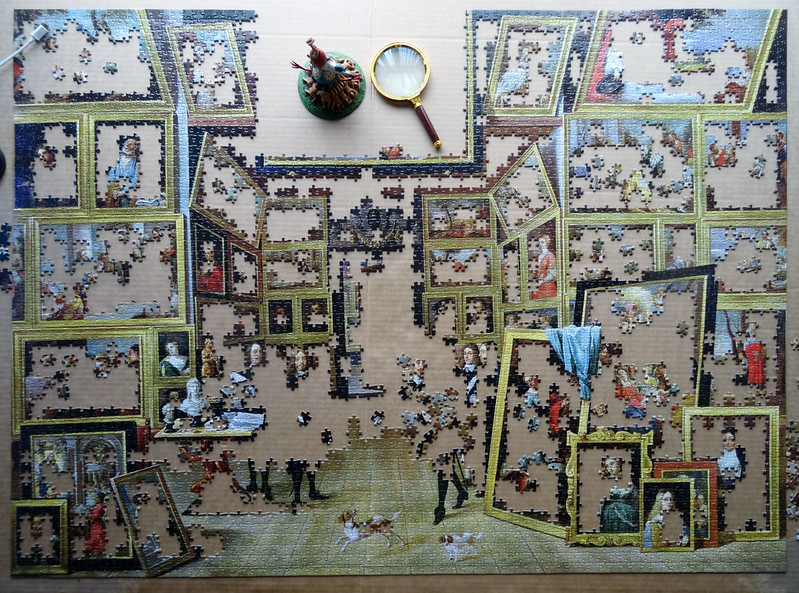

A late edition is this 4K Tomax I am currently working on. Tomax 400-029 – Archduke Leopold-Willem in his Art Gallery in Brussels (4K)

I’ve only done a few hundred pieces, and it may prove to be the hardest of them all, which will clearly demonstrate a point if indeed it is.

If you compare this Tomax to the Educa, you will see that while they are identical in subject (both “gallery” puzzles) it wouldn’t be unreasonable to presume that the Educa would be much harder, because it is both 25% bigger, and is a much darker and less detailed image. While both these things are true, what the box pics don’t tell you is the cut. The Tomax cut is diabolical, and that trumps the other factors.

Why is it diabolical, and why is this ‘cut’ thing so vital you ask? I guess we can deal with that in detail another time. ?

PM: Fascinating! And I totally agree with you. I have often said I would rather tackle the 24,000 piece Life: The Great Challenge or the 42,000 piece Around the World puzzles than some of the really difficult photomosiac puzzles or the World’s Most Difficult double-sided puzzles that are 42x smaller and nothing but baked beans or blades of grass!

Thank you for your time again this evening, Gus. It was a pleasure, and I look forward to hearing more from you on various puzzling topics soon.

8 thoughts on “Puzzling Conversations: Gus – Part Two”

I realized that difficulty is subjective after lending one of my favourite puzzles to a friend and was shocked to find she thought it was insanely difficult. The image is a Kandinsky painting, and I think it’s pretty easy (this is the puzzle: https://puzzler1909.home.blog/2019/04/11/balancement-2017-11-05-2009-03-03/). In this case, cut isn’t a factor, the cut is excellent, so it must be the image. Personally, I’m sometimes in the mood for a difficult image, but I never want to do a difficult cut. If pieces fit where they don’t belong when you place them in a corner formed by to other pieces that are correctly placed, I’m not interested (exception if the wrong piece is identical to the correct piece so that you can just switch them when you’re done). I know not everyone feels like this, I recently talked to a puzzler who told me she enjoys the extra challenge of pieces fitting pretty much everywhere. I definitely don’t ?

I think you are right, Nicola. It is very subjective. This Kadinsky doesnt look too hard to me either with the exception of perhaps the large amounts of white and possibly the black pieces. Otherwise it has quote a bit of color variation. I would take this any day of the week over the 1000 piece puzzle that is nothing but baked beans. I agree that image choice has a lot to do with difficulty, but if you combine a relatively hard image with a very random cut where weirdly shaped pieces can fit together in very unusual way, then it becomes nearly impossible.

I would actually take a random cut over a grid cut where pieces fit where they don’t belong. A random cut makes for a good kind of hard (assuming pieces only fit where they belong), but a bad grid cut is just frustrating. To me, at least 🙂

Interesting point of view. I think the random cuts are much more difficult myself then a grid cut. I guess maybe because I have had so much morebexperience with grid than random. For beginning puzzlers it can be a little overwhelming too I think when they arent like “typical” piece shapes.

Thanks for sharing!

Hey Nicola, it’s interesting that you mention Kandinsky. I recently did one of his (first one) and I commented elsewhere that I found it so easy that it was almost boring.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/145768213@N06/49122821032/in/album-72157711869924183/

What it comes down to really is this… how much experience you have (and that does NOT mean how many puzzles you have done) and how many strings you have in your bow, determines how ‘easy’ a puzzle will be. In other words, how many strategies or ways of assembling a puzzle you have. Short illustrative point. A guy I know who does big (30-50K) puzzles as a matter of course, recently struggled to do a 1K puzzle of a relatively simple image. Why? Because it was random cut, and he had never done one before. I felt his pain, because as it happens, I was doing the same puzzle at about the same time.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/145768213@N06/49088164167/in/album-72157711705983616/

He showed us a progress pic after 9 hours, and he was stunned at just how little he had done. Is he a bad puzzler? No sir. He is a super fast, top notch expert, and I mean expert, BUT, he had no experience with this cut and thus, it stopped him cold… for a while.

Many people seem to think that speed and numbers of puzzles completed are the things that make you better. They aren’t, and the reason they aren’t is that because if you use these things as your sole measure, you will get worse, not better, because you will choose images that are fast to assemble, and your desire for speed will make you impatient and give up on anything that you can’t do quickly. The way to get better is to do different styles of puzzles, and learn the different strategies you need to do them. This Tomax I am working now requires a different strategy to pretty much anything I’ve done before, and so, I am ‘learning’ from it, so when I need to employ this particular strategy next time, I will be a lot better at it.

There’s a post on Facebook now about the way a person is assembling a puzzle, where he picks up a piece, and places it within the frame, in its position, and repeats until done. The poster commented on how well this works. I replied that it works were it works, but will fail completely in far more cases than it will succeed. She disagreed. I posted a pic of 1000 pieces of solid blue, and she replied that he wouldn’t touch it. In other words, she admitted that his method will fail, which isn’t what she said to start. Understand that this isn’t to poke fun at her or him, but to try to help them understand that if they want to get better, then they have to adapt and learn, not just keep doing the same thing over and over.

Finally, as for pieces ‘that fit pretty much everywhere’, I’ve seen that claim made a lot of times, yet the pictures that accompany it rarely back it up. The pics almost always show ‘pieces that have been put in the wrong place that clearly don’t go there’. There are exceptions of course, in fact, I had one myself recently, and I have to say, I did enjoy it punishing me

Ah, one more thing, I just reread your comment and you said something that needs to be cleared up. You said, “In this case, cut isn’t a factor, the cut is excellent…” which makes me think that what you are reading into my definition of ‘cut’ is not correct. The ‘cut’ means the style of the pieces, not the quality of them. Grid cut (like my Kandinsky), or random cut, like my Lempicka, and variations within these, are what I mean by cut. There is a third cut called ribbon (or strip) but that one isn’t used any more (I don’t think!).

I THINK you are talking about the precision of the cut, which means, ‘the degree of confidence that you have when placing two pieces together, based solely on fit and feel’. A puzzle that is imprecise, means the pieces will fit most anywhere, where with a precise cut, they only go where they go. Strangely enough, precision and tightness aren’t always the same thing. It is quite possible for a puzzle to be precisely cut, yet not be overly tight.

Anyway, we all like what we like and we do what we do. As I have said many times, there are only two ways to do a puzzle, the right way, and the wrong way. The definition of right is, ‘you finished it and enjoyed it’ and the definition of wrong is, ‘you didn’t finish it’.

Enjoy

I don’t think becoming better at doing puzzles is a goal of mine, but I’m sure you’re right that doing different kinds of puzzles is the key there. I’ve seen some rather silly guides on how to do a puzzle that assume you can use the same strategy on every puzzle, like always doing the edges first.

You’re right that I tried to refer to the precision of the cut. You could see cut precision as a continuum, with pieces where you need scissors to place a piece wrong at one end, and pieces that really do fit anywhere on the other. I definitely prefer puzzles with a precise cut, and I stop finding puzzles enjoyable (probably) long before it is actually impossible to know if a piece fits. There are many puzzles where it is still possible to know what piece goes where if you use all the information available and are really careful, but I don’t find it enjoyable. Ability to recognize whether a piece really fits is, of course, also something that you learn and, I’m sure, get much better at if you practice. A friend who is not a puzzler was once moved to place a few pieces of a Ravensburger I was working on. They were all wrong and I took them out after she left. These photos aren’t good enough to tell if the pieces actually fit anywhere, I think, but here are a couple of puzzles that I gave up on for that reason: https://puzzler1909.home.blog/2019/02/10/unfinished/

I actually think not finishing is sometimes the right thing to do 🙂 But definitely, if you’re not enjoying it, then you are doing it wrong. Thank you for your interesting thoughts on puzzles!

Oh, and I’ve done your Kandinsky, too, and enjoyed it very much!

Glad you enjoyed the Kandinsky. It is sitting behind me in puzzle limbo. It is kinda growing on me. Re what you said about visitors ‘helping’. I wouldn’t let a visitor near a puzzle I was working today, but back in the day, I didn’t mind, and like you, I would come back and see all these pieces in the wrong place, and say to myself, “what is this person thinking? It not only doesn’t fit, it doesn’t match!”. Weird 🙂

As for precision…

I define it as “the level of confidence you have when placing two pieces together, with only one point of contact” (image matching aside). When a puzzle is has a precise cut, you have a very high level of confidence when you place the pieces.

When the cut is imprecise, you cannot ever place a piece with another, even when you have two or even three points of contact, with confidence. Here’s an example of an imprecise cut. 🙂

https://www.flickr.com/photos/145768213@N06/49448329021/in/album-72157711935245623/

Sometimes, to learn, things have to be explained. Some people can learn, others can’t, or don’t want to. Ultimately though, it is a personal thing. I don’t have a goal per se to get better, but I am a naturally curious person, which means I like to learn, so getting better just happens automatically 🙂

Lucky eh? 😛